I always enjoy the Globe and Mail’s “chartapalooza” that Jason Kirby curates at the start of each year. After all, a picture (or in this case a chart) is worth a thousand words, and if you follow me you know I like a good chart.

So here’s my (unofficial) contribution of two charts and two maps (why not?) that Canadian political and business leaders may wish to consider as they navigate the stormy seas of 2026 and beyond.

The rise of the Electrostate.

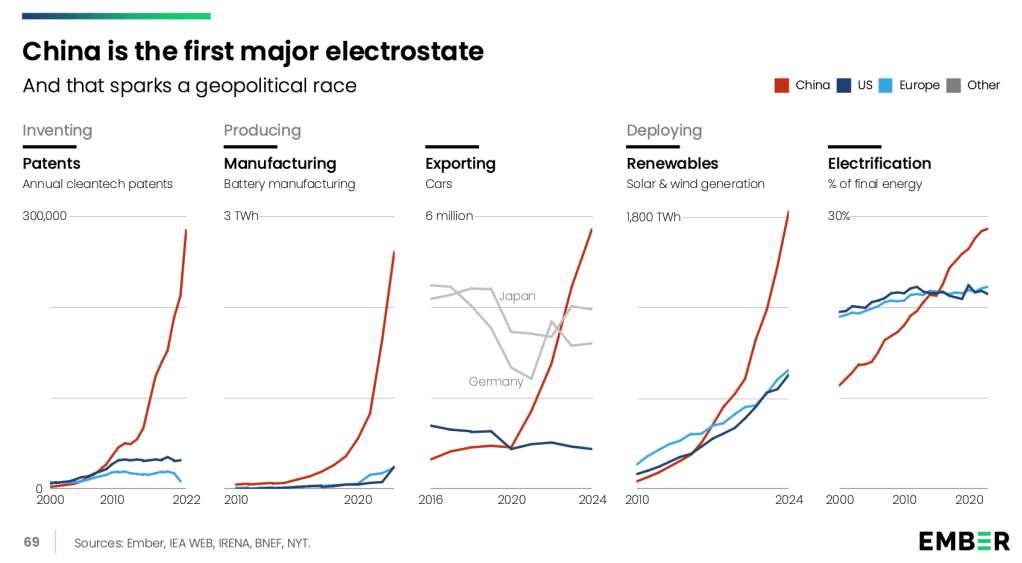

In 2025 the term “electrostate”—and China’s ascension as the world’s first electrostate—began to hit the mainstream. Put simply, an electrostate is a nation that invents, produces and deploys clean energy technologies that produce (e.g. wind and solar) and use (e.g. EVs and heat pumps) electricity, with electricity meeting a growing share of energy demand through increased electrification.

But with China as the most dominant electrostate, and the United States doubling down as a petrostate, analysts observe that “What is emerging are two competing models of energy and influence—one anchored in the enduring logic of hydrocarbons, the other in the accelerating promise of electrification. At stake is not just the future of energy systems, but the contours of geopolitical power in the decades ahead.”

And as we enter 2026 this competition between China, the most powerful electrostate, and the United States, the most powerful petrostate, was identified by the Eurasia Group as the second-biggest global risk. As they put it, “The spread of cheap electrotech is good news for the world. It enables more resilient energy systems, creates new opportunities for AI deployment, and maintains momentum for the global energy transition…China bet on electrons. The US bet on molecules. In 2026, we’ll start to see who was right.”

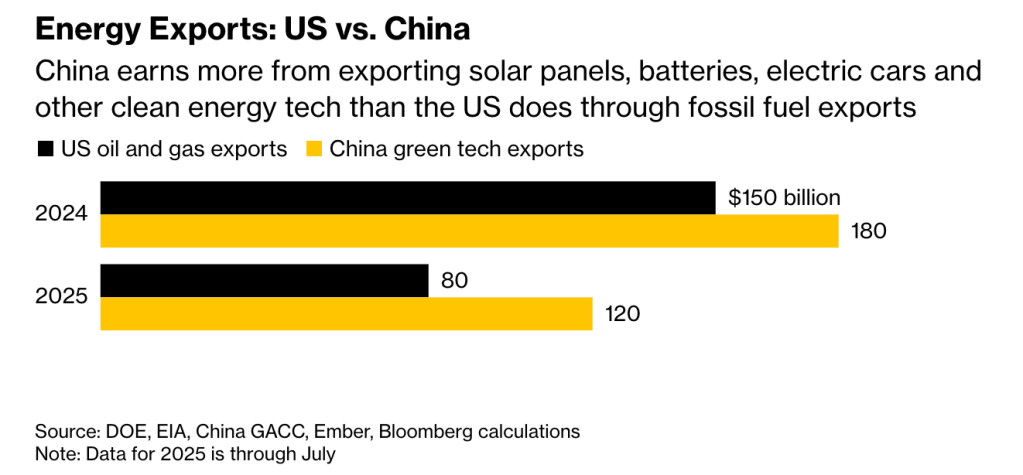

This takes us to my second chart.

The odds appear to favour the Chinese electrostate.

In the battle for energy export dominance, as Bloomberg reported (also the source of this chart) “For now, there is a clear winner: China.” While the US hit a record in oil exports in 2024 at $150 billion, China’s clean technology exports were $30 billion higher. And through the first half of 2025 this trend held, even though technology prices for solar panels and batteries had fallen sharply.

But China isn’t just exporting these technologies, they are rapidly building out production capacity in other countries. As a report from the Net Zero Industrial Lab found, “A rapid acceleration in overseas investment by Chinese green technology manufacturers is reshaping the global clean-tech landscape. Since 2022 alone, investments have surged past USD 220 billion, spanning sectors such as batteries, solar, wind, new energy vehicles (NEVs), and green hydrogen. These investments now reach 54 countries across every major region.” Hot spots of investment include Indonesia (a linchpin for nickel-rich battery-material projects and new solar lines), Morocco (cathodes and green-hydrogen for EU supply chains), Gulf states (solar module and electrolyser manufacturing backed by sovereign offtakes), and Hungary, Spain, Brazil, and Egypt (sector-specific hubs for batteries, hydrogen, or mixed clean-tech plays).

Which brings us to two important maps.

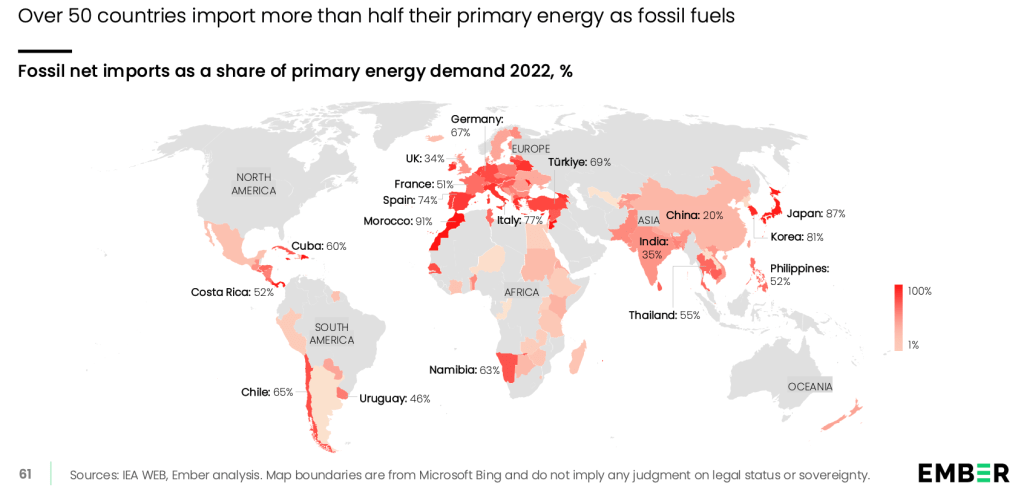

Fossil fuel import dependency is widespread and very expensive

In Canada we are blessed with an abundance of energy of all kinds, which enables us to meet our own needs and be a significant exporter. Three-quarters of the global population reside in nations that are fossil fuel importers, and one-quarter spends over 5 percent of GDP on fossil fuel imports. The geopolitical, security, and economic risks of this dependency are myriad, from exposure to price volatility and inflation to trade deficits, vulnerability to political coercion, and compromised sovereignty. It’s not surprising, then, that import-dependent nations will jump at the opportunity to get off the fossil fuel import rollercoaster—whether by design or consumer defection (for the latter, see Pakistan).

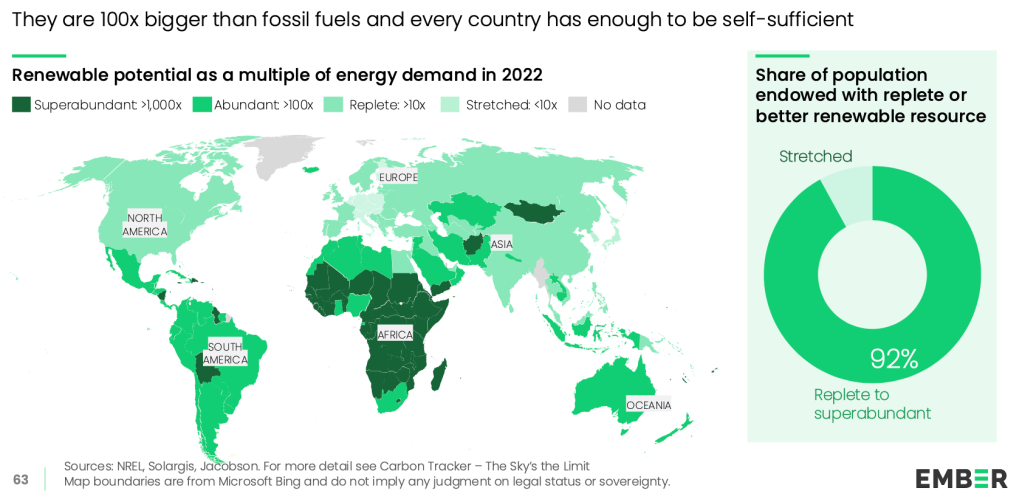

Given access to the technologies to harness it and use it, renewable power is available to all

In 2025 it became evident that while much of the western discourse around the energy transition hinged on commitments to climate action, the on-the-ground reality driving investment in and adoption of electro-tech (wind, solar, batteries, EVs, heat pumps etc.) often boils down to economics and energy security. In addition to China, Latin America, Africa and South East Asia are leapfrogging past the OECD’s share of wind and solar. Brazil, Pakistan and India ranked amongst the top-5 solar PV importers from China.

As Bloomberg columnist David Fickling wrote, “There’s a comforting story that oil bulls like to tell themselves to stave off worries about the future: While the privileged few in Europe and California might have lost their minds over electric vehicles, billions of drivers in the Global South are readying themselves to provide the next wave of petroleum demand.” But according to the IEA, EV sales increased by 60% in developing countries as a whole in 2024.

Prime Minister Mark Carney believes “Canada has a tremendous opportunity to be the world’s leading energy superpower, in both clean and conventional energy.” In recent months the broad brush strokes of what this means for conventional energy—oil and gas—are becoming clearer. But what it means to be a clean energy superpower—and what it will take to grow into this—has yet to be defined.

As evidenced by the charts and maps above we had best get working on this.