This essay was originally published in the May-June edition of Policy Magazine.

It’s been more than a year since Russia invaded Ukraine, precipitating a range of regional and global crises, not the least of which is “the first truly global energy crisis.” It has disrupted both energy supply and demand, resulting in energy price spikes, while damaging and shifting longstanding trading relationships.

As a result, we are confronted by new questions about the prospects for a global shift from fossil fuels to clean energy to combat the climate crisis: will a renewed focus on energy security slow or accelerate the energy transition? And what will this mean for global efforts to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions?

To answer these questions and understand the implications, we must do our best to cut through the “fog of war” that has descended on the energy transition. As Carl von Clausewitz, a 19th-century Prussian general, said: “War is the realm of uncertainty; three-quarters of the factors on which action in war is based are wrapped in a fog of greater or lesser uncertainty. A sensitive and discriminating judgment is called for; a skilled intelligence to scent out the truth.”

To say the state-of-play on the energy transition has been dynamic is an understatement, but it is possible to cut through the fog and see where things stand, where we’re headed, and what it might mean for Canada.

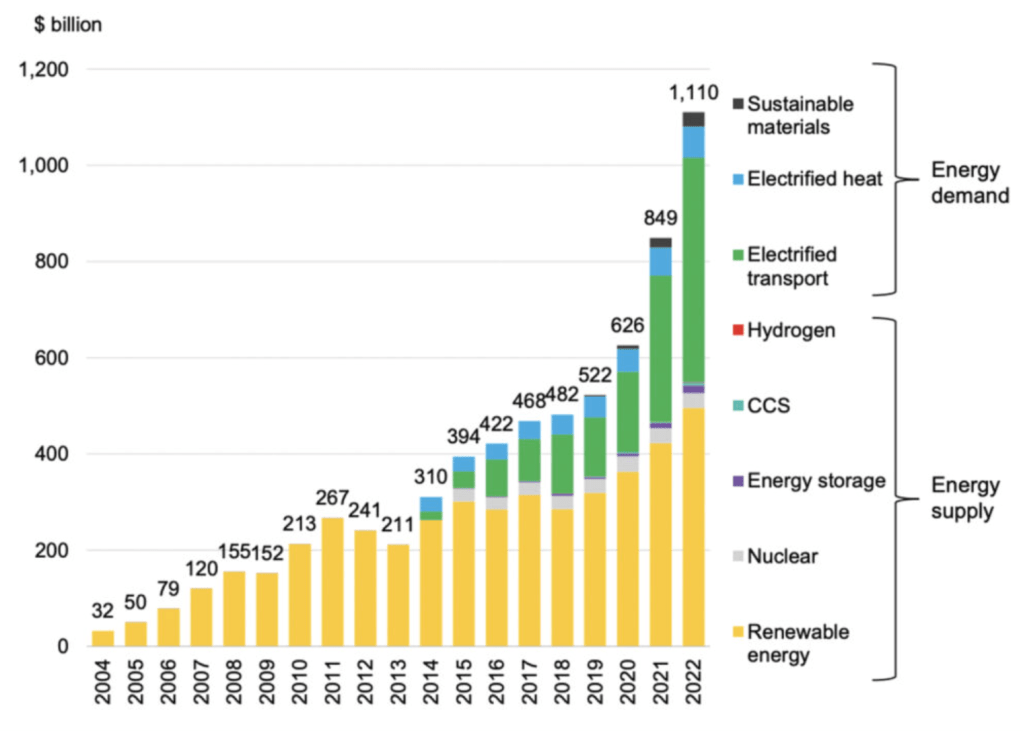

According to an analysis by BloombergNEF, last year marked the first time that as much money was invested in replacing fossil fuels as in producing more coal, oil and gas, with each garnering around US$1 trillion (Figure 1). On the clean energy side of the ledger, this was a 31 percent increase over investment in 2021. The biggest recipients of this capital were solar and wind (US$495 billion, up 17 percent) followed close behind by electric vehicles (EVs) (US$466 billion, up 54 percent). As for where this capital was deployed, nearly half (US$546 billion) was in China. If European countries are considered together, they tallied US$180 billion, and the US was home to US$141 billion.

Figure 1: Global investment (US$) in energy transition by sector, BloombergNEF

The energy transition investment total increases if you add investments in expanding and strengthening power grids (US$274 billion), clean energy supply chains and manufacturing (US$79 billion), and the $119 billion raised by clean-tech companies in equity financing. All included, investments driving the energy transition topped US$1.6 trillion last year.

Globally, wind and solar accounted for a record 12 percent of global electricity in 2022, and power sector emissions may have peaked, according to the think tank Ember. Drilling down into some specific examples, by the end of 2022 India was home to 199 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar capacity (for context, Canada’s entire electricity system is about 150 GW), and they have announced plans for tendering 50 GW of renewable energy capacity per year for the next five years (i.e. adding up to 250 GW). Japan and South Korea both re-visited their energy plans in light of evolving energy markets and their own net-zero commitments and now aim to reduce reliance on both coal and LNG while boosting nuclear and renewable energy capacity. Electric vehicle adoption is taking off too, fueled by more selection (in 2022 more than 300 models were on offer), and by the end of 2022 a cumulative total of 27 million EVs were on the road, displacing more than 1.6 million barrels per day of oil in 2022, according to BloombergNEF.

With this progress, even if incremental, the delayers, who say climate solutions are too expensive, and doomers, who say it’s too late, can safely be discounted. As the International Energy Agency has found, while carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions grew by 0.9 percent in 2022, the rise in emissions was well below global GDP growth of 3.2 percent and would have been three times higher had it not been for strong growth in clean energy.

It seems quite evident that the war in Ukraine, like the COVID-19 pandemic, won’t derail the energy transition. To the contrary, European leaders have found a solution to their energy trilemma — achieving energy sustainability, affordability, and security — and it isn’t LNG, it’s a decarbonized energy system.

As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen put it, “The quicker we switch to renewables and hydrogen, combined with more energy efficiency, the quicker we will be truly independent and master our energy system.” Within weeks of the Russian invasion, the EU unveiled the REPower EU Plan, which took the previous target of a 25 percent cut in natural gas use by 2030, relative to 2020, and more than doubled it to 56 percent. And the plan is working. Take heat pumps, for example, which replace gas boilers. In 2022, Europe led the world with 41 percent growth in heat pump sales (compared to global growth of 11 percent), with nearly three million sold. It seems Putin has done the near-impossible: make heat pumps sexy.

It seems quite evident that the war in Ukraine, like the COVID-19 pandemic, won’t derail the energy transition. To the contrary, European leaders have found a solution to their energy trilemma — achieving energy sustainability, affordability and security — and it isn’t LNG, it’s a decarbonized energy system.

Closer to home, the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the United States—perhaps better thought of as the Industrial Revolution Act — will not only transform the American energy system, it will cause ripple effects around the world. With an estimated public investment of US$400 billion — in the form of tax incentives, loans, and grants — the IRA is expected to drive more than $1 trillion in private investment into the production and deployment of clean energy solutions, including (but not exhaustively) renewable energy, batteries, EVs, more efficient consumer appliances, hydrogen, and carbon capture and storage.

The head of investment at Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures, a climate solutions investment fund, said the IRA would lead to the creation of 1,000 new companies; 100,000 jobs were created in the six months since its passage on the way towards an estimated 9 million jobs. Hardly a week goes by without an investment announcement with links back to the IRA. Clichés like “game-changer” and “tipping point” are not overstatements. As Melissa Lott, director of research at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy, summed it up: “It is truly massive. It’s industrial policy. It’s the kitchen sink. It’s a strong, direct and clear signal about what the US is prioritising.”

Here in Canada, the course the federal government (but not all provincial governments) is charting is clear, as evidenced by its clean energy-oriented spring budget — effectively designed to compete with the IRA in a significant but targeted way — and ongoing efforts to secure new net zero-aligned industrial investments. Canada can and must compete and collaborate with our allies, most notably the Europeans and Americans. There is good reason to be bullish, and to double down: we have a head-start with our relatively clean electricity system and numerous renewable energy and technology options for its necessary expansion; we have the critical minerals needed for the energy transition and rank second in battery supply chain competitiveness, and we are home to entrepreneurial innovators, including the dozen companies that made the 2023 Global Cleantech 100 list.

Looking to the future, it’s clear that countries are poised to continue making progress in their efforts to pivot to clean energy and reduce GHG emissions, with implications for coal, oil and gas. As Fatih Birol, head of the IEA, wrote, “Russia’s efforts to gain political and economic advantage by pushing energy prices higher have spurred a major response by governments — not just in the EU but in many countries around the world — to speed up the deployment of cleaner and more secure alternatives.” As a result, projections in the IEA’s flagship annual World Energy Outlook released in late 2022 are already out of date. Where it foresaw, for the first time, a peak in fossil fuel demand before the end of the 2020s, the agency’s newest data indicates that peak is moving even closer.

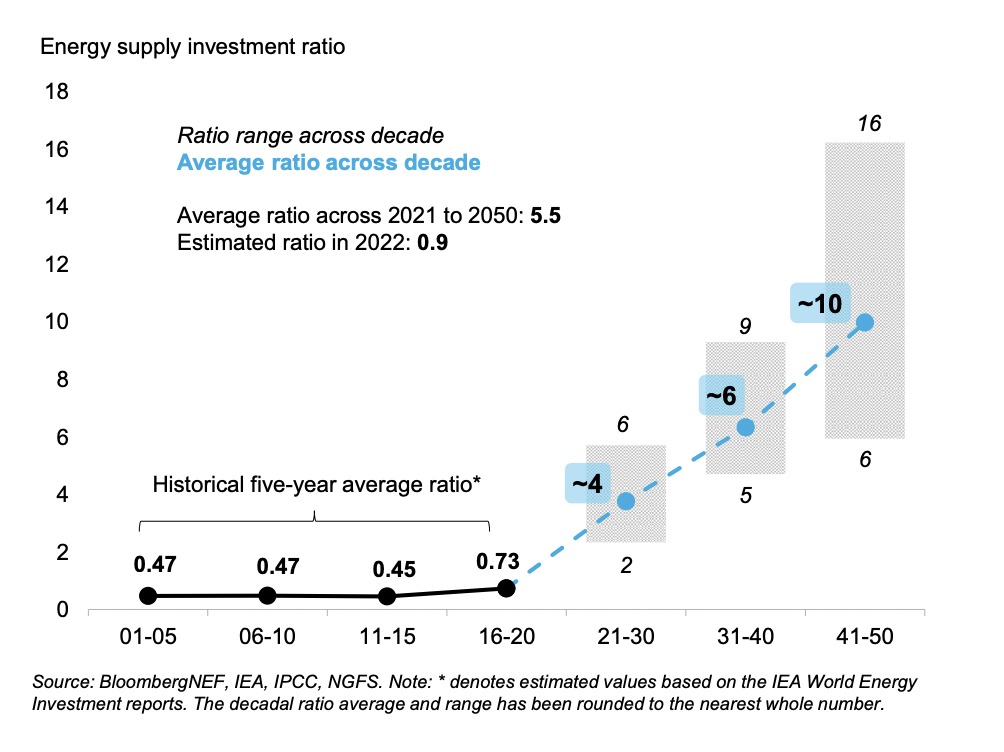

In the face of this optimism, it must be acknowledged that not every country or company is headed in the right direction, nor is the flight path to net zero emissions by mid-century likely to be a smooth one. While clean energy investment now matches fossil fuel investment, BloombergNEF finds that the investment ratio needs to be 4:1 (Figure 2) to ensure an orderly transition, in which growing clean energy supply offsets the required decline in fossil fuel supply. The Royal Bank of Canada, whose CEO advocates for an “orderly transition” is only achieving a ratio of 0.4:1.

Figure 2: Range of decadal energy supply investment ratio, 2001-2050, BloombergNEF

There are and will be challenges (see: critical mineral supply), setbacks (see: high natural gas prices perpetuating reliance on coal-fired power in Pakistan), and deviations from the transition (see: BP, Shell and Exxon backing off their climate targets). Such is the turbulence of transitioning to new supply chains, the power of path dependency, and the constraints on incumbents.

But the momentum towards net zero is building — 128 countries representing 88 percent of emissions, 92 percent of GDP and 85 percent of the world’s population have made net zero commitments — and the technology and investment trendlines are clear: the energy transition is accelerating. As the IEA’s Birol notes, “With this in mind, the push by some companies and governments to build new large-scale fossil fuel projects is not only a bet against the world reaching its climate goals — it is also a risky proposition for investors who want reasonable returns on their capital.”

The challenge for Canadian policymakers, business, and finance leaders — for our climate performance and economic competitiveness — is to decide where to place our bets, which will determine where we find ourselves when the fog of war on energy transition finally lifts.